I feel almost silly including the motor drive in a list of “B-Side” topics, as they were quite necessary for my professional work decades ago. It’s strange that they would now be considered an oddity or relic of the past, yet here we are.

Motorized auto-winding mechanisms for 35mm film cameras have been in use for over 50 years. Popular with professional photographers, the motor drive effectively increased the speed at which the film was advanced and shutter cocked, making the camera ready to take another photo. Motor drives started out as accessories that attached to the bottom of the camera, with a coupling device to engage the in-camera mechanism. Early units were attached to a separate battery pack by a cable.

In the late 1970s we started seeing SLR cameras with built-in motorized drives, and the film advance lever as we knew it slowly disappeared in mainstream camera systems. Frame rates continued to increase and winding the film by hand became an almost archaic practice among typical SLR users. The sound of a photo being taken as portrayed in music and cinema became the sound of a motor drive, rather than the click of a shutter. Folks my age might recall the intro to Duran Duran’s “Girls On Film” and “Freeze Frame” by the J. Geils Band.

Pigeon Lady in Puerta Del Sol, Madrid Spain.

Many rangefinders seemed to buck that trend, maintaining traditional form and function, although motor drives were available for some. At the time of this writing, several manufacturers are making 35mm film cameras, and most of these have traditional winding levers or film advance wheels. Perhaps the act of physically winding the film is part of the nostalgic romance of analog photography.

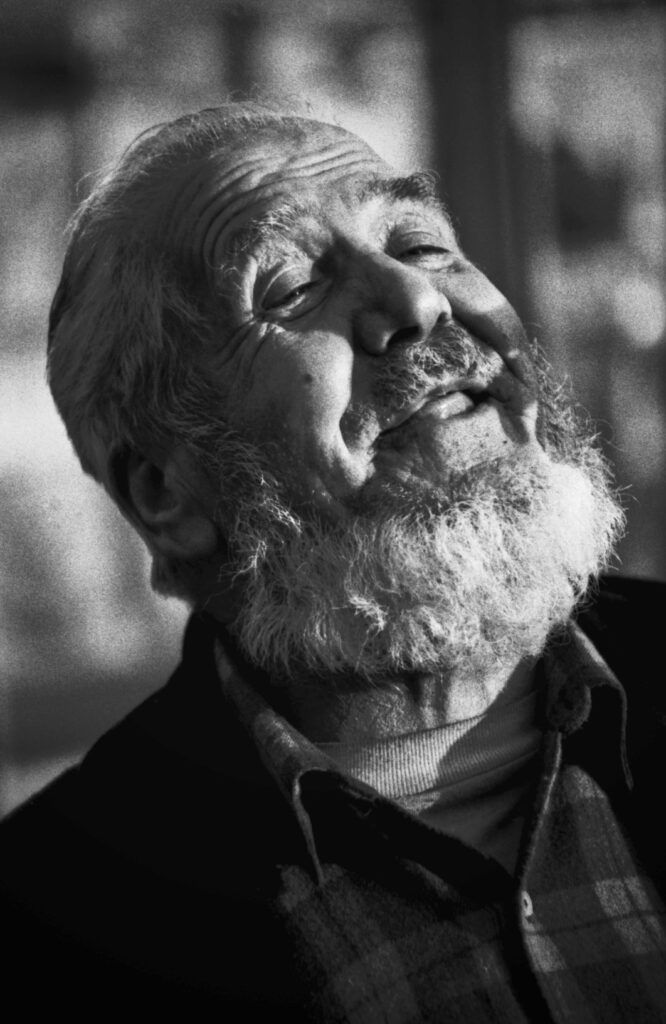

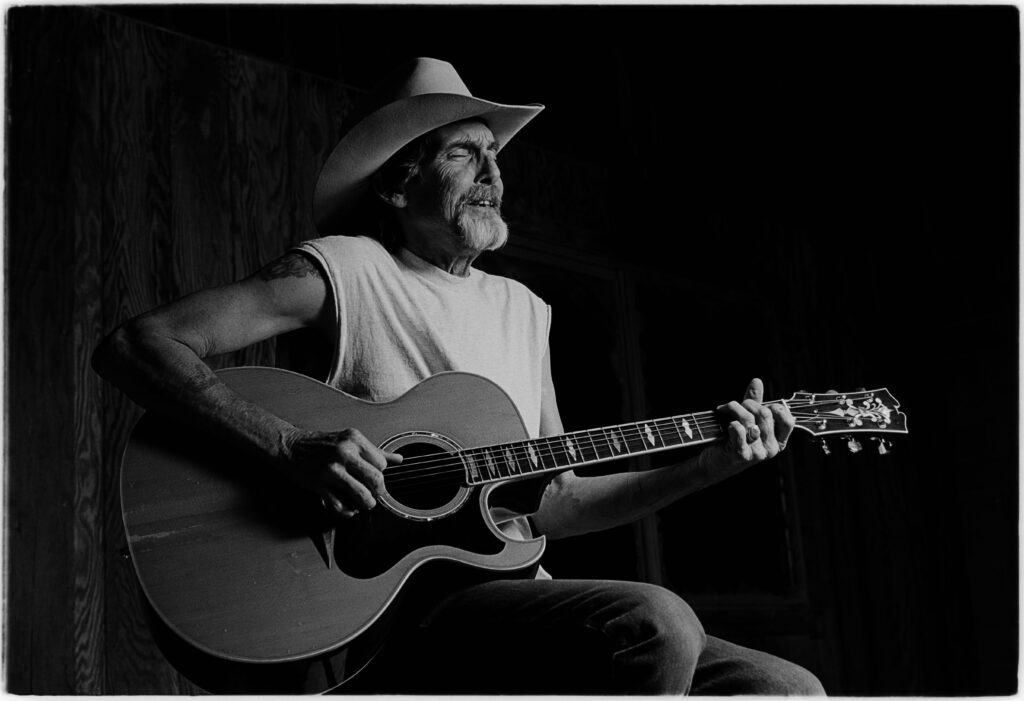

Some SLR motor drives had a generous grip with a second shutter release button for comfortably shooting in the vertical position. With this second button, extended photo sessions in vertical orientation became a breeze. This eliminated the need to reach over the top or fold one’s arm under the camera, and instead use a much more relaxed and natural shooting stance. Vertical format photos were the predominant orientation for print work like fashion and other portraiture.

I recall showing up to college sporting events with copious quantities of film and batteries, and burning through them quickly. Fast follow-up shots were critical, as sporting events could be very fast-paced. It was a common practice to anticipate the play, start shooting, and hope for the best. The method I used then seems horrifically wasteful now, but was necessary to increase the odds of getting the shot. I wasn’t the only one; there was often a chorus of motor drives on either side of me during a dramatic play. Eventually I became better at anticipating the action, but still shot lots of film.

Are motor drives on vintage cameras relevant today? To be honest, I like having them, but I rarely use them. I used to carry one camera body with a motor drive and a backup body without it every day. I like the way they increase the overall grip area and feel of the camera. However, they also increase the weight, as most require up to eight AA batteries. I would likely not carry one around on a casual stroll in the park. If I anticipate a rapidly changing scene in which timing is critical, I would bring one along.

The last time I used one seriously was a couple of years ago in the studio, photographing a dancer. A very large fan just outside the frame was blowing her dress and long hair, and at times the movement was just right. My studio strobes didn’t require much time to recharge, so speedy follow-up shots were possible. The convenience of keeping my eye to the viewfinder, a solid grip and fast follow-up shots were the reasons I chose to use it.

Another scenario that benefits from a motor drive is when I am panning a moving subject. Once I have the movement of the camera in sync with the subject, I can fire off sequential frames without breaking stride. My panning motion can remain steady, and I can get several times the amount of frames on subject. Again, this increases the odds of getting just the right shot.

Whenever the dynamics of the scene are fluid or unfolding rapidly, the motor drive earns its keep. Pedantic purists may clutch their pearls at the thought of relying on a motor drive to capture the “decisive moment”, but it could be argued there are times you need to tip the odds in your favor. At the end of the day, the shots you get are the ones that matter, and nobody should care if you used a motor drive to get them.

Puerta Del Sol, Madrid, Spain.

At some point there is a sobering realization that at today’s film prices you could be spending $4 per second with that button held down. One could ask, “Is it worth it?” Well, thirty-six shots of a longhorn bull standing in a pasture may not be a cost-effective use. A sequence of images of an aging grandfather hugging his grandchild for the last time may be priceless.