It was 1987, and the photographic world was changing. I suppose “changing” is an understatement, as the advent of autofocus SLRs represented a significant evolutionary step in camera engineering. Minolta had led the industry with their Maxxum line, but Canon was not far behind.

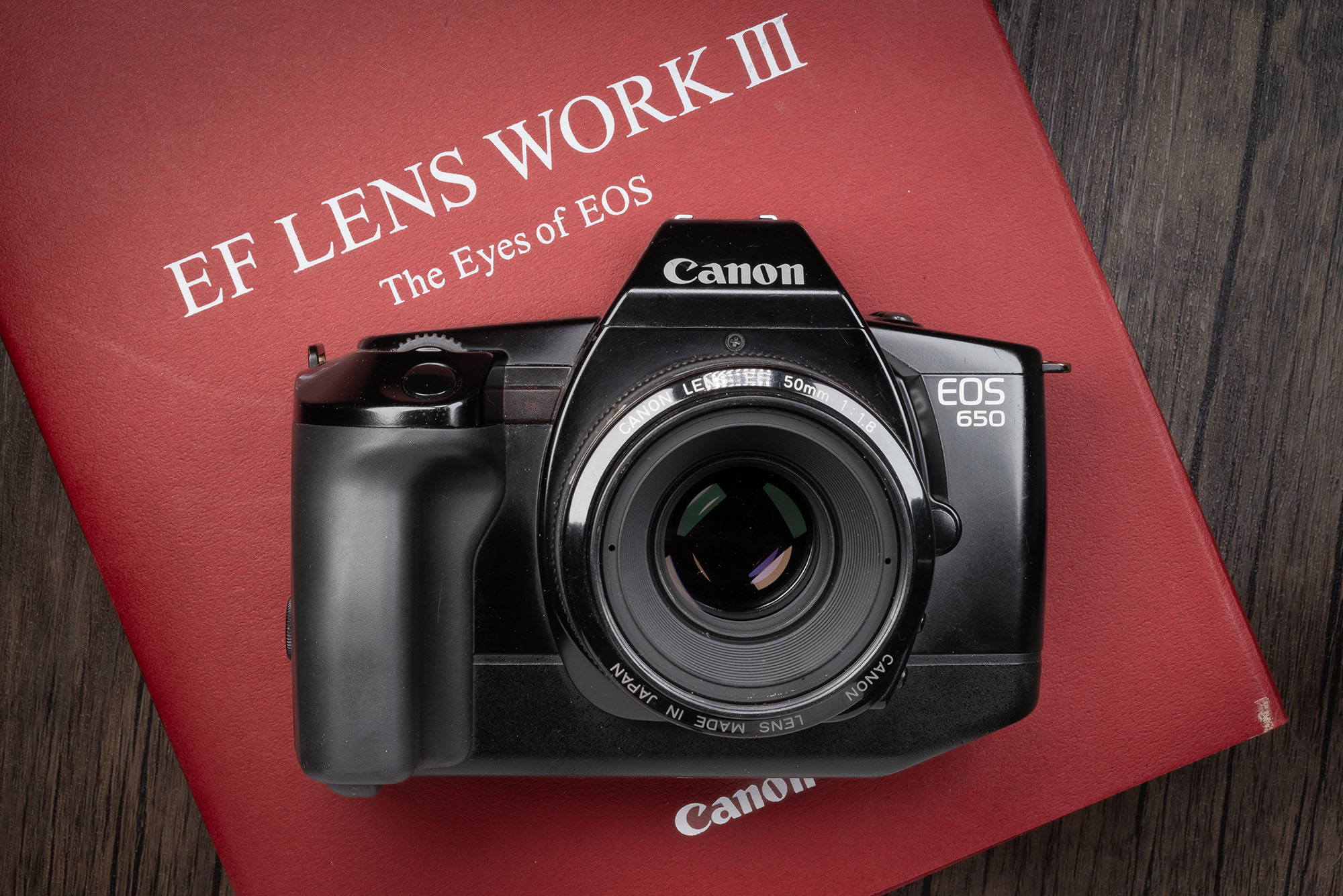

Canon redesigned their cameras with a new mount supporting autofocus, advanced electronics, and communication between the lens and the body. Plastics continued to replace metals, as the chemistry and manufacturing practices evolved at the same time.

Automatic program modes had been around for a while, which allowed the photographer to turn over some of the decision-making process to the camera. Autofocus took this a step further.

I remember watching the industry change with keen interest as to where it was going. Autofocus was apparently here to stay, even though I had gone backwards from autofocus to manual. The new cameras were seemingly capable of being used as glorified point-and-shoots. Did the photographer really need to do anything but point the camera in the right direction?

I suppose it made the SLR more accessible to the beginner, allowing one to start making correctly exposed and focused photos without studying the manual or understanding the mechanisms. That’s exactly how I began. Of course there was still room for creative control, and I was not content with full automation.

Thirty-something years later, that technological forward leap had net effects that are still readily evident in today’s cameras. Even though I didn’t embrace Canon’s EOS line at the time, I continued to watch through the 1990s as Canon and Nikon dominated the technological race and drove the industry forward.

Minolta may have pushed Canon harder than expected, as Canon had just released the T90 the year before. While highly regarded, the T90 fell into the shadow of the EOS system and never really got the attention it deserved.

Canon’s EOS 650 was the first of its breed. In ancient Greek mythology, Eos is the goddess of the dawn, bringer of light, sister of the sun god Helios and moon goddess Selene. Surely Canon knew that when they came up with the acronym for “Electro-Optical System”. At least I hope they did.

Microprocessors controlled all the functions. Canon had developed the “BASIS” sensor and claimed it led the industry in precision. I can believe that, as I had yet to see a failure to lock on to the subject except under very demanding conditions. I recall my Maxxum 5000 being slower and less precise.

Controls largely evolved from dials to buttons during this era. The EOS650 has one lonely, little dial to turn, and that only switches the camera on. Options on this dial are “On”, “On with beeping”, “Full Program” (regardless of mode setting), and off. Ironically, dials are back en vogue.

The rest of the functions are controlled by a few buttons. There is a manual available online that explains all of the functions. The main controls on top are a Mode button, an Exposure Compensation button, and the control wheel. Available modes are Manual (M), Aperture Priority (AV), Shutter Priority (TV), and Depth.

Going in reverse order: Depth mode allows you to set a front and a back focal plane, and the camera will adjust the aperture to get it all in focus. It also sets the shutter speed accordingly. Shutter Priority allows you to choose the shutter speed and the camera chooses the appropriate aperture. Aperture Priority is just the opposite; you choose the aperture and the camera chooses the shutter speed. Exposure compensation adjustments can be made by pressing the “EXP COMP” button on the left top and turning the wheel.

This brings us to Manual.

When I first switched to “M”, I couldn’t find any meter reading to guide my choices. That’s because it isn’t there. Turning the control wheel changes the shutter speed. Pressing the little unmarked black button on the left side of the lens mount while turning the control wheel changes the aperture. It is also the depth of field preview button.

The manual provided the missing link. There is a small button on the left side of the lens mount, below the DOF preview button labeled, appropriately, “M”. Upon pressing that button, one of three codes appears in the LCD at the bottom of the viewfinder. It also appears on the top LCD.

Those codes are as follows: CL, oo, and OP. These are commands to adjust the aperture to get proper exposure for a given shutter speed. CL stands for “close” the aperture. OP stands for “open” the aperture. “oo” is correctly exposed. As you turn the control wheel with that button pushed, it cycles through the aperture settings and changes the code as indicated by the meter. Turning the wheel without pushing the button adjusts the shutter speed.

Once I had that in my head, I was able to use the manual mode with the meter. I really can’t call it a fully metered manual mode however. This requires that you set a preferred shutter speed and then adjust the aperture until the meter is satisfied. Also, if you switch to a different mode, it forgets the settings you made. Any time you switch to “M”, it reverts to a default setting of 1/125 on f5.6. At some later point in the EOS dynasty, this was rectified.

The little black button behind the top LCD is the “Partial Metering” button, which acts as a fairly broad spot meter. By pressing this and half-pressing the release button, a reading is taken just from the center circle in the viewfinder. An asterisk appears in the viewfinder LCD and the exposure is locked in until the photo is taken or the finger is lifted from the release button.

At the bottom of the back, there is a small door with a magnetic closure. This hides four buttons that allow you to rewind film, choose autofocus modes, film advance modes, ISO override and and check the battery level. There are five functions in four buttons. Pushing the autofocus and drive buttons together allows the ISO override. Changing those settings requires pressing the button(s) and turning the wheel.

Some of those controls are less than intuitive, but are not overly complicated. Putting this camera in historical context, all these new features were quite exciting. Even today, the functions are still relevant. It really lacks nothing, except perhaps a more convenient manual mode.

Moreover, it is a pleasure to use. This generation of cameras marked an era of dramatically evolved ergonomics. It feels good and solid in the hand, something that I value. Its grip area is generous and the index finger falls just where it should. Current prices for the body only are around the cost of a modest lunch for two, and EF mount lenses are plentiful.

This camera showed up to the party wearing a “nifty fifty”: the ubiquitous EF 50mm f1.8. There was film still in the camera, and a quick peek through the film chamber window revealed that it was Kodak Tri-X. There was about a half a roll remaining, according to the film counter. I had no idea if the film was still good, but there was no point taking a chance on wasting the beloved emulsion.

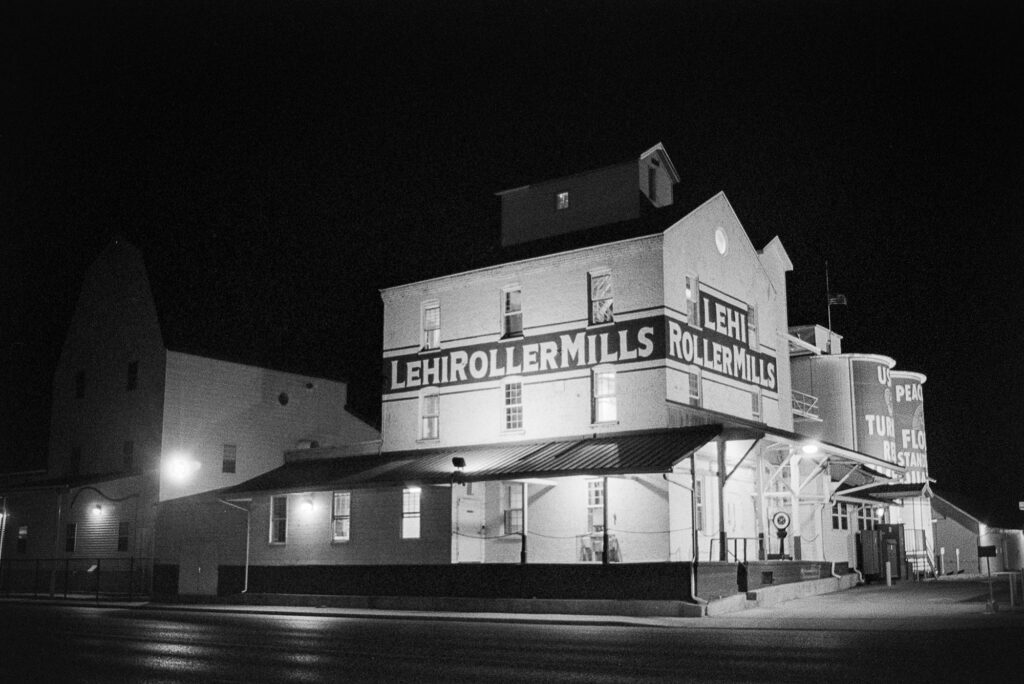

I shot the remainder of the roll on a trip through northern Utah. After finishing the roll at the famous Lehi Roller Mills (where scenes from the movie Footloose were filmed) I brought the camera back to the hotel room for a thorough cleaning, inside and out. Despite evidence of having been used, it has held up remarkably well.

There was also an EF 28-90mm kit zoom in the bag. I already had the Vivitar Series 1 19-35mm lens I reviewed here as well as a Sigma 75-300mm zoom. A trip into the mountains to see the quaking aspens in their fall color glory demanded a range of focal lengths. I packed it all into a Red Oxx Rucksack fitted with a camera bag insert. I picked up two of my nephews and we headed up the canyon for a great afternoon outing. I didn’t wait long to develop the film, as I was excited to see how the camera performed.

I smiled and nodded as I unwound the wet film from the spool and hung it to dry. I saw consistently good exposure and perfect frame spacing. After taking off the excess water, I checked the images with a loupe, which revealed sharp images. Then I let them dry in peace, confident that I had spent the day behind a worthy camera.

Specs:

Designation: Canon EOS 650 35mm SLR

Introduced: 1987

Manufactured: Japan

Lens Mount: Canon EF

Weight: 700g (24.7oz) with battery

Shutter: Vertical metal focal plane, electronically controlled.

Shutter Speed range: 30-1/2000 second plus bulb

Flash Sync: 1/125 second

ASA range: 25-5000, DX coded with override option

Hot shoe: Yes, with dedicated TTL flash contacts

Meter: TTL 6-zone evaluative, partial (spot)

Modes: Manual, AV (Aperture Priority), TV (Shutter Priority), and Depth (explained above)

Battery: 1 x 2CR5

Self-Timer: Yes

DOF Preview: Yes

Mirror lockup: No

Multiple exposures: No