Perhaps the universe was trying to convince me that half frame 35mm cameras aren’t all trouble. That had largely been my conclusion after losing several fights with Olympus Pen and Trip cameras. As much as I love the idea of a half-size, half-frame camera, only a couple of Mercury II cameras had come my way and decided to actually work. I’ll write about those at a later date.

This Canon Demi came my way via a charitable thrift shop, and came as a total surprise. It sat in its original black leather case, ignored and unloved. I had heard about the Demi line of half-frame Canons, but never had the occasion to use one. I had little hope of it actually working, given my history with other mid-century compacts.

I pulled it from its case and carefully cocked the shutter with the film advance lever. The action was beautifully smooth. Turning it around, I looked into the lens as I tripped the shutter. The signature sound of a healthy leaf shutter was barely audible above the background noise. I paid the modest price and left the store a bit giddy. I couldn’t wait to load it up and start shooting.

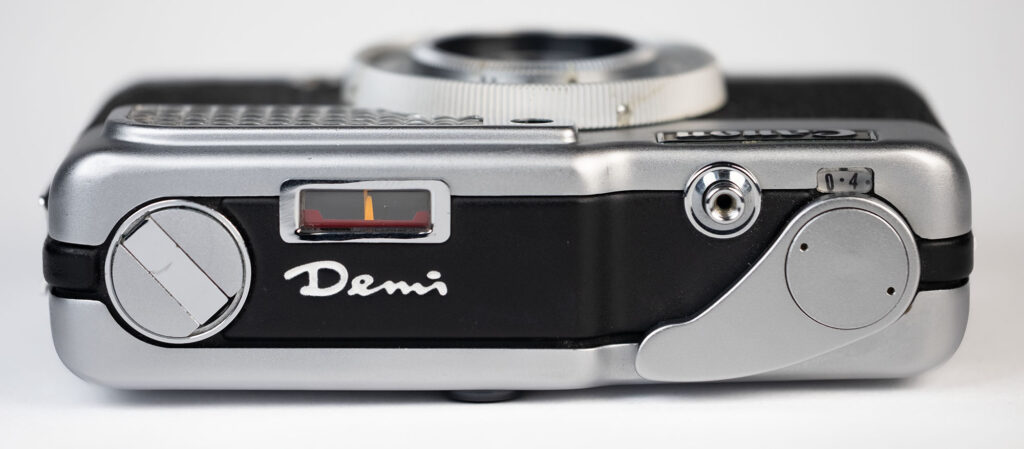

You will notice that it has a selenium meter, which is responsible for correct exposure. Selenium meters are a high-probability point of failure in vintage cameras. They always make me a bit nervous, particularly in cameras that don’t have any manual exposure controls. Many lose their sensitivity as they age. To my surprise, this one still works perfectly.

Exposure control is an odd yet simple system. The selenium meter is always “on”, as it has no switch. On the top there is a small window with a match needle indicator. The outermost ring around the lens controls the combination of shutter speed and aperture. Turning this ring moves the exposure needle in the top window. Lining up the two needles results in a correct exposure.

Exposure range is from 1/30 at f2.8 to 1/250 at f22. That range covers EV 8-17 at ISO 100.

These combinations are locked in, as there is no independent control of shutter speed and aperture. That’s pretty basic, but consider that it is not a professional system. For the traveler with basic photo needs, this suffices. Film speed, Bulb and Flash Sync settings are on the same ring.

The innermost ring is the focus. This is a zone-focus camera with “head, group, mountain” graphics on the scale to indicate distance. There is a plate on the back with specific distances relative to the points on the scale. I’ve had no problems with missed focus. It’s pretty intuitive.

The brilliant Keplerian viewfinder is located just above the lens, close enough that parallax correction would be very minor at the closest distances. It offers no information except framing. It is remarkably bright and crisp, despite its diminutive size. The viewfinder alone contains four lens elements and three prisms. That alone tells me something about the intent of the designers.

I half-expected the lens to be retractable, but it isn’t. It sits nearly flush with the body, making this camera truly pocketable. The 28mm f2.8 lens acts more like a “normal” lens on a full-frame camera. It contains five elements in three groups. Again, not a cheap construction.

Elegant design principles went into this camera, inside and out. Some may see it as just a tool, like a spanner or a hammer, unconcerned with its looks as long as it does the job. I appreciate the intricate dance of engineering and aesthetics. The tool needs to work, but there’s no reason it can’t look good doing it. The alternating black and chrome features attract the eye. Even the chrome finish alternates between matte and polished.

This is the first of the Demi series, appearing in 1963. It entered the half frame market after Olympus released the Pen in 1959. By the time it came to market, there were already twelve competing half frame cameras. Nonetheless, it proved to be popular. Sold with a wrist strap, cap and leather case, it was a handsome kit. Subsequent models introduced changes to reduce weight and add features.

Speaking of weight, the Demi does not feel delicate. It feels like a proper camera. Weighing in at 386g (13.6oz), it feels compact yet dense. Metal dominates its construction, with a chrome plated brass body and very little plastic on the exterior. The film takeup spool and sprocket are plastic, however.

Thankfully, this camera needed no mechanical repairs, as I would have been hesitant to even try. It did, however, require light seals, as most vintage cameras do. I was surprised at how extensive the light seals were. It required much more material than expected, but it is light tight now.

Half-frame (18×24 mm) means double the number of exposures on the same length of film. I underestimated how long it would take to shoot 72 frames. My tendency with film is to avoid wasting it. Being deliberate with only one or two frames of a subject results in a long time between loading and rewinding the roll. It saw action on several trips over a few months.

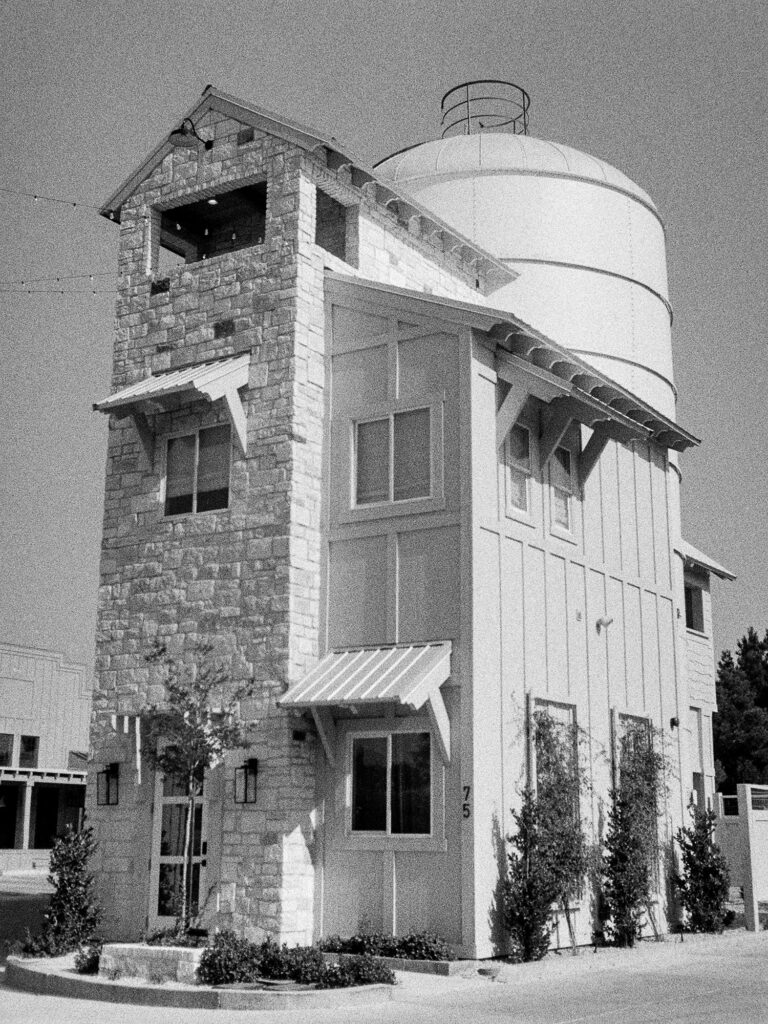

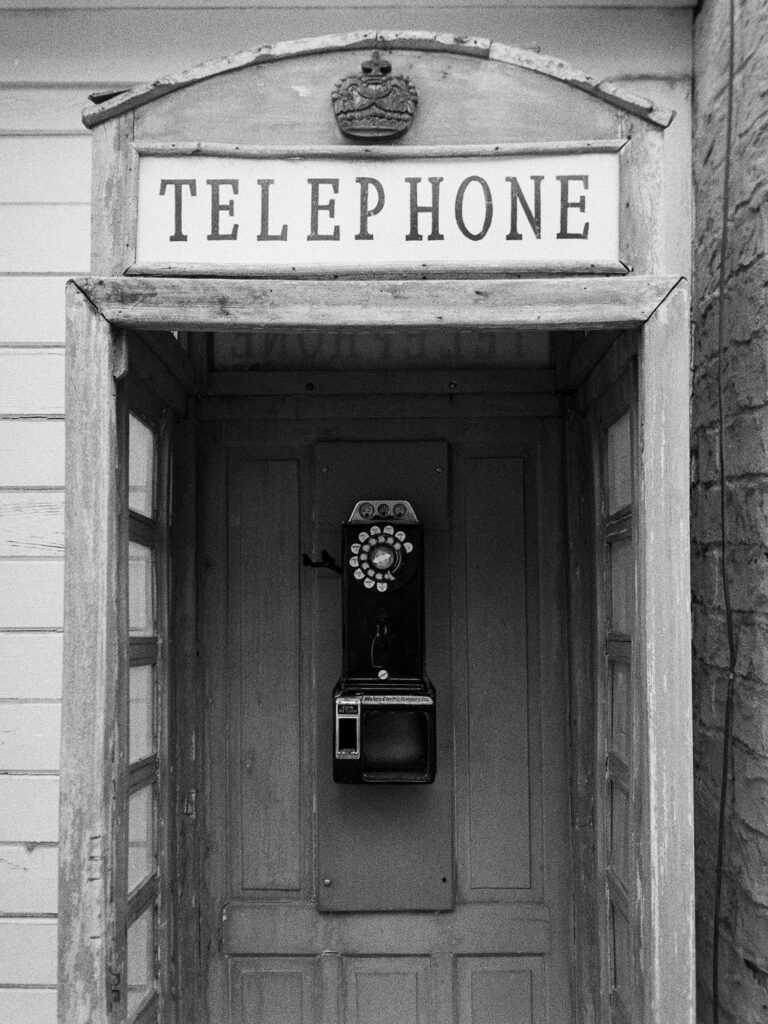

Before setting out on a journey with an unproven camera, I try to at least shoot a short test roll to make sure it works. Such was the case with this one. I also try to wait at least until the freshly developed film is fully washed to check it, but I couldn’t resist a peek. I unspooled a bit of still-wet film to see good frame spacing and exposure, and felt pretty good about life at that point. The black and white images are from that short test roll of Kentmere 100.

Further confirmation came later when I hung the full color roll to dry and saw 72 good images. The Canon had performed admirably and earned its own pocket in the camera bag.

Why half frame? Putting this camera in historical context may shed some light on the reason for half frame camera development and its subsequent success.

For decades, families went on vacation with folding cameras using 120, 620, 616 and other formats. The number of photos per roll was relatively small. Color print film was only twenty years old, and was still gaining momentum. Black and white negative film still dominated that market. Photo labs, particularly with the larger formats, offered contact prints or small enlargements with negative film. Prints would go into photo albums, only to be trotted out at holiday family gatherings years later.

Life, however, is in color, and these were the glory days of Kodachrome. Vacation film rolls were slipped into their yellow and red mailers and sent off to the Kodak lab for processing. A couple of weeks later, a package arrived with the slides tucked neatly into little storage boxes. Out came the projector, the roll-up screen, the pie or popcorn, and the ritual of the family color slide show began.

Whether slides or 8mm film, this was “home theater” at its best. Friends and family came over, watched the slide show, had a good laugh, and that brought closure to the summer. Decades later, the projector would get pulled from the top shelf of the hall closet, dusted off, and the next generation could almost time-jump into their parents’ childhoods.

Half-frame cameras, in this scenario, offered twice the fun. Image quality was secondary to the experience itself. The purpose of the exercise was not to produce fine art, but to record an event that could be shared and treasured for years to come.

I had to remind myself of this when suddenly new half-frame cameras started appearing on the market, with such illustrious names as Pentax and Kodak. Film photographers now expect and embrace imperfection and grain. Combine that with the per-frame cost of shooting film, and suddenly half frame makes a lot of sense.

Back to the Demi: I have been pleasantly surprised with the images. It really performs, even in difficult lighting. Of course the grain is going to be twice as visible at the same degree of enlargement as a standard full frame. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect from the lens, but I was willing to accept a suite of optical aberrations and flaws, given the age and nature of the camera.

After establishing that the camera would shoot, I intentionally used it in a variety of lighting situations. It handled full sunlight, open shade, and mixed lighting quite well. Shooting into a sunset, I half-expected a blowout of flare and ghosting. Didn’t happen. I even trusted the meter for that shot, and it delivered.

In fact, this camera delivered everything I asked it to. I have zero disappointments so far, a rare situation in which to find myself. I suppose I could list several shortcomings, such as a lack of manual controls, limited ISO range, absence of interchangeable lenses, lack of state-of-the-art matrix metering, no focus confirmation, and so forth. That, of course, would be silly. It is what it is, and it does what it does. And, it does so beautifully.