In a conversation about classic cameras, somebody invariably invokes the name Leica. Historically, the brand has been associated with high quality optical equipment for nearly a century, and Leica played a pivotal role in bringing 35mm photography to mainstream society. The first Leica 35mm cameras were designed by Oskar Barnack and the first prototype was made in 1913. In 1925 the Leica I was introduced. It was an immediate success and gave rise to an evolving lineage of cameras now known as “screw-mount” or “Barnack” Leicas. Various improvements and features came gradually, culminating in the last of the Barnacks, the Leica IIIg, which was produced until 1960. This camera (IIIc) was built in 1946 or 1947.

Specs are as follows:

Leica IIIc 35mm rangefinder camera

Shutter: Horizontal cloth curtains

Shutter Speed Range: 1 Sec. to 1/1000 Sec. with B and T

Rangefinder: Coupled, patch type

Lens mount: 39mm threaded

Self-timer: No

Light Meter: No

Flash Sync: No

Automatic Anything: No

This is a camera for photographers who don’t mind taking their time, who accept and even enjoy the slow, methodical process of taking a photo. That said, it is still faster and easier to deploy than many cameras that came before it. (Ironically, I still find it less complicated that the endless menus on my Nikon DSLR or Sony mirrorless.) Upon loading and using the camera, some features we would now consider odd become apparent. The film leader should be trimmed using a cutting guide, resulting in a longer narrow section. The film leader is inserted into a removeable take-up spool first. Then the film cartridge, leader and take-up spool are pushed into the bottom of the camera, sliding the film between the pressure plate and the film gate. The long leader helps ensure positive engagement with the sprockets and prevents binding. The bottom plate is replaced, a few frames are shot and advanced, then the film counter on the advance knob is manually reset to zero. It is now loaded and ready to go.

With the film advanced and the shutter cocked (this is important), the exposure can be set. Aperture is set on the lens, and the shutter speed is set on the body. Sounds typical, but with one oddity: The slow speeds (1/30 sec. down to 1 sec. plus T and B) are changed on a dial residing on the front of the camera. This separate gear train is engaged when the top shutter speed dial is set to “30-1”. The top dial controls the speeds from 1/40 sec. to 1/1000 sec. The photographer sets the shutter speed appropriately, then proceeds to compose the image. To focus on the subject, there is a small window on the left through which can see the double image rangefinder patch. Focus is adjusted with the lens ring until the two images line up. If the whole rangefinder image is blurry, the diopter lever mounted by the rewind knob can be adjusted as needed. Then one must shift the eye to the right to see through the simple viewfinder to compose the photo. The shutter can then be released to take the photo.

While it seems like a lot of steps to just take a photo, it still involves the same mechanisms of focus, aperture, and shutter speed. After a while, the order of operations starts to become comfortable. The net result of this complexity is that it forces one to slow down, think, and be deliberate about making a photograph. For some, this amounts to an improvement in their images.

Some of the 50mm lenses common to the screw-mount Leicas are collapsible. These include the Elmar, Summitar, Summar and Summicron. The Elmar f3.5 is particularly compact and retracts nearly flush with the body, resulting in a very pocketable camera. The lens shown above is the Summitar 50mm f2. Each of the lenses has a particular character, and I will review the lenses that I have later. I enjoy them all. Excellent compatible screw mount lenses were made by several other manufacturers, particularly after WW2.

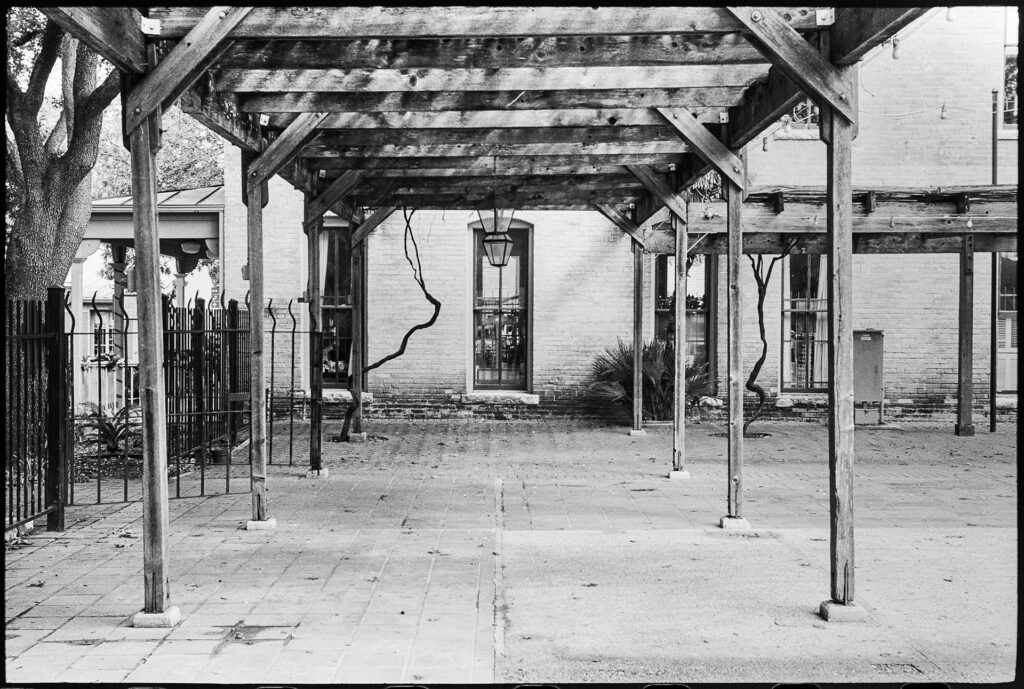

Leica produced a dizzying assortment of accessories. Among them were viewfinders that mount to the cold shoe on the top plate. The built-in viewfinder shows the same angle of view as a 50mm lens. Lenses of other focal lengths were available, and a separate view finder was required to compose with each one. Despite the native 50mm viewfinder, accessory viewfinders of the same focal length became popular. Shown in the first photo above is the (funkily code-named) “SBOOI” 50mm bright-line viewfinder mounted in the cold shoe. It takes the strain off the eyes and improves the overall experience. Focusing must still be done in the rangefinder (unless you are an amazing estimator of distance), but composing the shot is much more pleasant using the SBOOI.

I acquired this camera and its Summitar lens at a local antique store. The shop owner had a hard time determining which model it was because of an aftermarket flash sync (PC) socket plate mounted to the front. This was a fairly common modification. I did not like the feature, because the protruding socket sat precisely where my fingers naturally rested when taking a photo. It was an irritation, and I had little intention of using flash with that camera. I decided to restore the camera to its intended state by removing the flash sync mechanism. This also required me to plug the holes drilled into the body with steel-reinforced epoxy, and install a new leatherette covering. It was easier than I thought it would be. The slow speeds were also gummed up with hardened decades-old lubricants. A little solvent and light machine oil took care of that. Fortunately, the shutter curtains were intact. The rubberized coating on the curtains often cracks as they age, forming pinholes that allow light to leak through.

Remarkably, repair services are still offered for these cameras and lenses. There are three (easily searchable) prominent Leica specialists that operate in the US, and several others that are quite capable. Feel free to email me for my recommendations if so inclined. Two of the components prone to fail after a mere 70 years or so are shutter curtains and rangefinder mirrors. Both are still available (as well as many other parts), and nearly any intact screw-mount Leica can be returned to a smooth working condition. Most screw-mount Leicas will benefit from a CLA service (Clean, Lubricate, Adjust). If one needs a replacement part requiring disassembly, it just makes sense to get the part installed as part of a full CLA package. These cameras were built well and built to last by highly skilled technicians, but require a little attention every other generation, give or take.

The adjectives used by Leica’s critics and detractors (such as fiddly, squinty, overly complicated, etc.) aren’t entirely unwarranted. Quite the contrary, in fact. Screw-mount Leicas are fiddly and squinty and a bit complicated looking. Lots of knobs and dials and rings and numbers are part of the charm, and they tell me I have total control over the image. For me, much of the user experience is about the haptics, or tactile feedback, and the sounds of using a mechanical camera. I love watching the shutter speed dial, the release button, and the rewind knob spin counterclockwise as I turn the film advance knob clockwise. If they are not turning, I know something is wrong. Even if I am not watching all the marvelous movement, I know everything is working correctly by the feel and tension of the gears and the sound of the shutter.

I apologize if this comes across as just another Leica love letter. Engaging in an argument over which old camera was the greatest does not make my photos any better. However, while applying a little intellectual honesty and self-reflection, I believe that by occasionally using these old mechanical cameras, my photography improves. They remind me to take my time, be deliberate and precise, be less dependent on programmed algorithms and more trusting of my instincts and experience.