The Nikon F represents a dramatic turning point in photography, one in which the SLR emerged as the camera of choice for professional photojournalists and serious hobbyists alike. Although it evolved from a rangefinder, the Nikon SP, and stayed true to well-established design principles, the F introduced modularity in a camera. The camera became a system with modular components such as metered and non-metered prisms, focusing screens, film backs and motor drives. Many of these options had already been invented and were in limited use with other cameras, but Nikon combined them into one iconic camera that launched a photographic dynasty.

The Nikon F rose to the top choice for professional photojournalists. It saw a great deal of use during the Viet Nam war, where it earned a reputation for durability and reliability under harsh conditions and professional abuse. It was also adapted for use on Nasa’s lunar missions, carried on Apollo missions 8 through 17. I’m speculating that it was chosen due to both its modularity and its reputation for reliability. The Nikon F was a hard-working, professional camera that could be counted on to get the job done.

Nikon introduced various iterations, mostly in the form of improved metering prisms. The first F model with a metered prism was introduced in 1962, named “Photomic”. This was a play on words combining “photo” with “atomic”. The “atomic age” was in full swing with buzzwords being employed in marketing. The Photomic was followed by the Photomic T, Tn, and finally the FTn, the last three of which had through-the-lens (TTL) metering. The final metered prism had center-weighted TTL metering which set the new standard for accuracy.

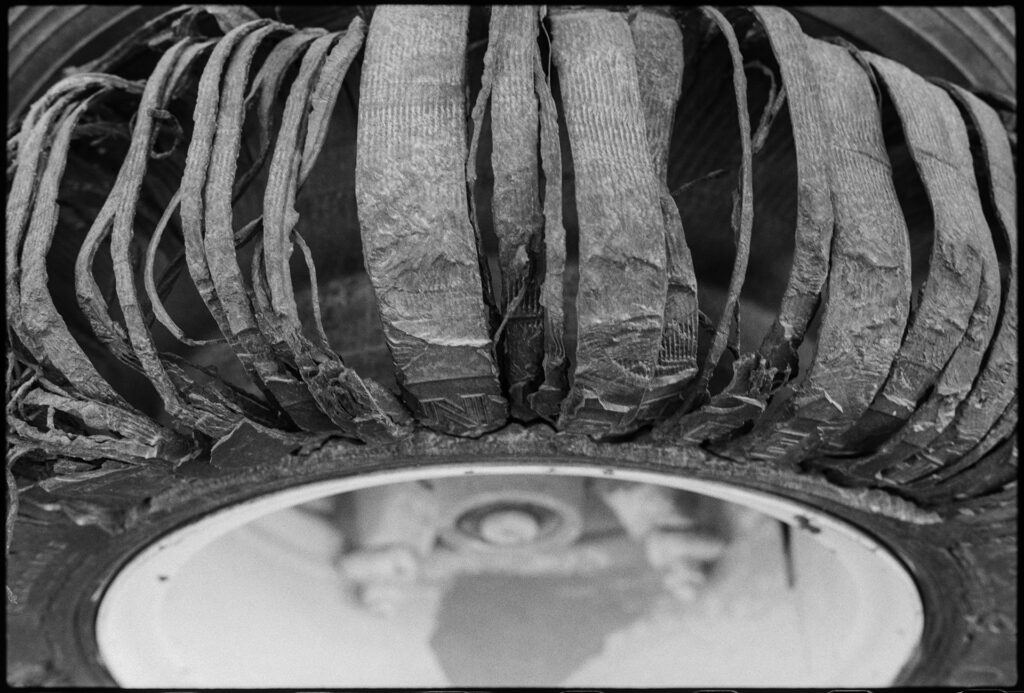

The first Photomic metered prism had some unique features. On the front of the meter there is a conspicuous eye, a photoelectric cell activated by raising a flag that blocks it when down. When the flag is up, the meter is on. Since the eye has a wide (75 degree) angle of view, it will naturally take in a lot of sky when shooting outdoors, and that can result in skewed meter readings. This is particularly an issue if one is using a telephoto lens. The solution to this came as a tube that screwed on to the eye, restricting its angle of view to that of a 135mm lens. This angle restrictor is stored on the side of the prism housing, screwed into the battery cap. An additional accessory included with this prism is the incident meter disk, also stored screwed into the battery cap. To take an incident light meter reading, one screws the disk onto the eye and takes a reading from the subject’s position, facing the position of the camera. This is a rare feature in SLRs, and the only one in the Nikon lineup.

Nikon’s granddaddy SLR has a purely mechanical shutter. Metered prisms have battery compartments to power the meter, but they operate independently of the shutter. It will take photos with or without batteries. I currently have two, an early 1962 Photomic, and a later 1967 FTn. Both are fun to use. Upon pressing the release button, there is a satisfying sound typical of a precision mechanical shutter. The heavy body absorbs much of the vibration caused by the shutter, but there is a mirror lockup function for use when that vibration may detract from a sharp image. For example, when shooting with the camera mounted on a tripod while using a telephoto lens, the mirror slap can induce some motion blur. It would be advisable to lock the mirror up after composing the shot. One quirk of this function is that it results in a blank frame in addition to the photo taken.

My first F, the later Photomic Tn, walked in the door as I was browsing a local antique shop. A man and his wife came in and told the shop owner that he has this old “Nokia” camera that used to belong to his father. It was in the original black never-ready case. He couldn’t make a deal with the shop owner, who gave me a nod to make a deal if I wanted it. (He knew I did.) It needed a good cleaning and lubrication, particularly in the metered prism, but it came out working perfectly.

The second one was a surprise. On a recent trip to Houston, Texas I just happened to be staying a few miles from the Houston Camera Exchange. I had a little boot money, and I wandered in to check the place out. I was met by Bernie, an energetic salesman who, despite my arrival 30 minutes before closing on a Saturday night, seemed happy to talk with another old film enthusiast. He dragged things out of the back room for me to check out, just for the fun of it.

I told myself that I already had a Nikon F and that I didn’t need another one. But why should I listen to an old fool that talks to himself? Besides, it’s not exactly the SAME model; that would just be silly. The shutter sounded good, I could see that the light seals had been replaced, and it was in remarkably good condition for an old pro-grade camera. I talked myself into it and I took the chance. Besides, he threw in the old leather never-ready case for free. I brought it back to the guest house where I was staying and cleaned it up a bit. My suitcase was already filled with studio lights and clothing, with no room for the new camera. Besides, I didn’t want it in checked luggage anyway. I realized that it was going to add a substantial amount of weight to my carry-on bag, but decided that I could use the extra exercise, and exercise is a good thing. Over the next few days it followed me from Houston to Kansas City, and then on to Las Vegas. Once home, I gave it a proper inspection and cleaning, inside and out. The shutter gave me a single problem early on, but worked itself out with a little exercise.

Both meters are a bit off, and I can compensate for that my adjusting the ASA. That said, I still prefer to meter a scene with a handheld incident meter, or with the light meter app on my iPhone, which generally agrees with all of my other meters. The alternatives to the long-discontinued PX625 mercury batteries are hard to find or expensive. I should probably buy the adapter that accepts readily available batteries and adjusts the voltage appropriately. I likely have a dozen cameras that use that battery, and I would have to move that adapter-battery set around to multiple cameras that use it. Frankly, it’s just easier to meter handheld. I accept that older in-camera meters are aging and often lose sensitivity, but as long as the camera body holds the film flat, lets in the right amount of light, and moves the film when I tell it to, I’ve got the rest covered.

Nikon F models are heavy and bulky, dramatically over-engineered cameras. That is part of their charm. It is the prism that announces the make and model in no uncertain terms. One can spot a Photomic from across the street. I am, however, on the lookout for a decent eye-level finder, or unmetered plain prism. I find the lines of both the F and the F2 much more aesthetically pleasing without the bulky metered prisms. In practical use, I don’t find the Nikon F to be an every-day camera. It’s heft and bulk dissuade me from carrying it around everywhere. The Nikon FM2n has been a more convenient companion. Having said that, it is fun to take a historically significant, iconic camera for a stroll every once in a while.

Specs are as follows:

Camera designation: Nikon F

Introduced: 1959

Weight: 30.8oz/872g (Ftn model; varies with options.)

Lens mount: Nikon F manual focus (Accepts all Ai and Ais lenses)

Shutter: Mechanical, horizontal titanium curtains

Shutter speeds: 1-1/1000 second plus B and T

Flash sync: 1/60 second

Film speed range: ASA/ISO Depends on prism

Features: Self-timer, DOF preview button, hot shoe, PC cord socket, motor-drive option, interchangeable viewfinders, backs and focusing screens