Zeiss Ikon made quite a few variations of their 120 roll film folding cameras with a system of model numbers I will not try to explain. There was indeed a system that made sense to somebody, but it read more like the Dewey Decimal system than a marketing strategy. In some markets, this camera was simply known as the Zeiss Ikon Ikonta II. Produced in Germany in the early 1950s, this was an affordable medium format folding camera that found a compromise between portability, quality and price.

My Ikonta is the smallest, most pocketable medium format camera I have ever owned. It was almost certainly intended as a consumer-grade camera , rather than a professional machine. For a 1950s tourist who wanted medium-format quality in a small package, the Zeiss Ikons delivered. Some of its cousins had coupled rangefinders, meters, and image formats from 6×4.5cm to 6x9cm. This model produces a square image at 6x6cm and has a simple viewfinder.

I recently found this quirky little gem in an antique shop in Las Vegas. Some of the moving parts didn’t move as well as they should have, but that was easily rectified with disassembly, cleaning and lubrication. Fortunately, the shutter mechanism didn’t require much work, and it came to life with a little exercise. After a couple of outings and a rapid learning curve, I have come to like it. Sort of.

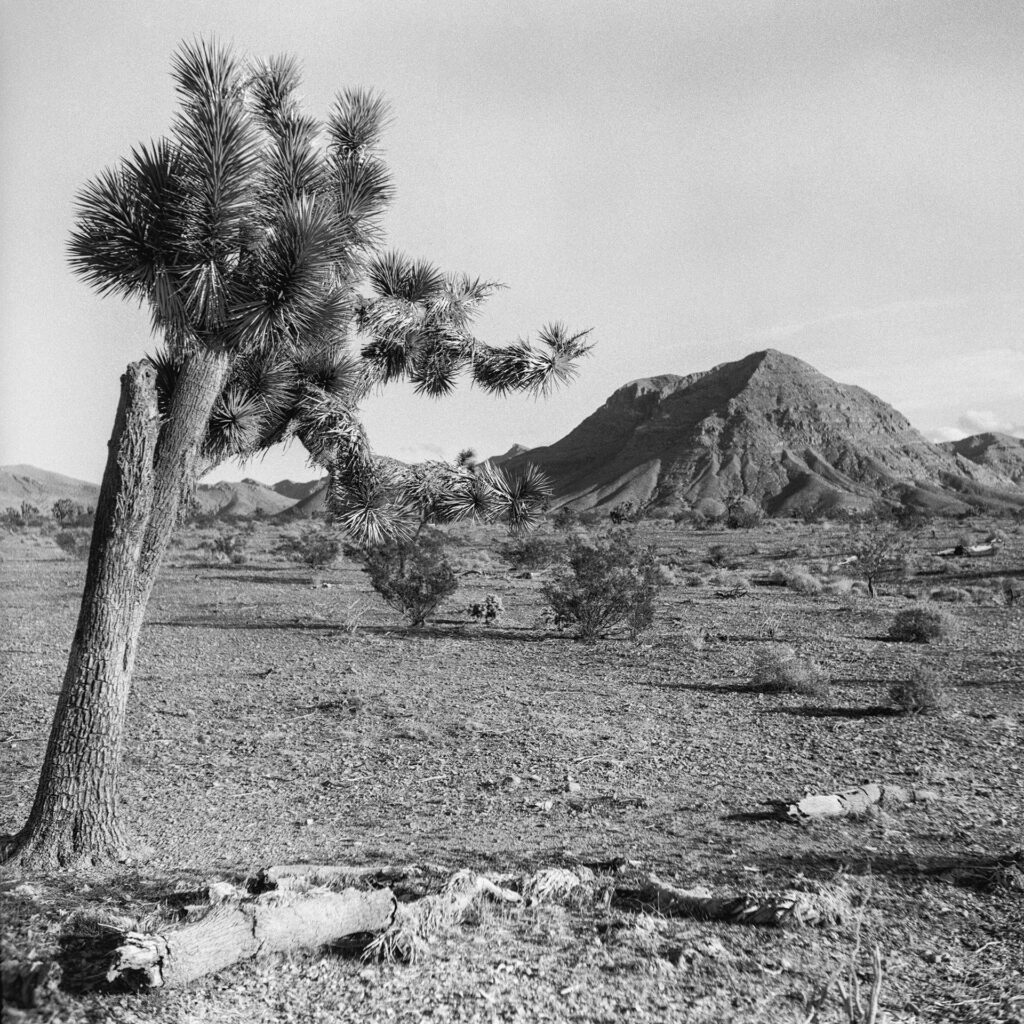

Knowing that I should approach every new camera with an open mind devoid of expectations, I still couldn’t help associating The Zeiss name and 120 film with ultimate quality. I had to temper that a bit after scanning my first roll of film shot with it. It is neither a Rolleiflex nor a Hasselblad. Image quality was respectable considering the compromises made for cost and portability. The lens is simple, with little optical correction we have come to take for granted. Since it is so light, movement while taking the photo is likely, and easily recorded in the images. This movement can come from simply pressing the shutter release button or vibration from the shutter mechanism itself. A tripod helps with the former but cannot entirely prevent the latter. Even with a sturdy Italian tripod and a shutter release, movement was apparent in a few photos. I am working on finding a sweet spot in which this is minimized.

Several times I have mentioned that lens sharpness is secondary to character, but sharpness is important nonetheless. I don’t want a blurry image regardless of overflowing character. This lens is capable of acceptable sharpness, particularly in the middle. The image gets a little soft and smeared in the corners, which isn’t really a surprise for a simple, lightweight lens from the 1950s.

Focusing with a camera lacking a coupled rangefinder is a difficult thing to get used to in the age of autofocus. One cannot see the image through the lens, as in an SLR. Nor does one have any mechanism for determining if the lens is in focus. There is a distance scale on the rotating front element, and I have verified that it is accurate. That said, in the field it is sometimes difficult to eyeball the distance to the subject. Zone focusing becomes the standard practice, relying on the depth of field at smaller apertures to ensure that the subject is in a distance range that falls into focus. For scenics and typical tourist shots, that works just fine. In the studio or for portraits outside, one may use an accessory rangefinder to determine the distance to the subject and set the focus accordingly. The closer to the subject, the more important accurate distance measurement becomes.

One quirk worth mentioning is the red dot indicator on the top by the shutter release. It is a small round hole through which one can see the status of the shutter release. There is a mechanism under the camera top that locks the shutter release button until the film has been advanced. This is ostensibly to prevent unwanted double exposures. If the dot is red, the film has been wound and the shutter release is armed. Upon taking a photo, the dot turns white. The odd part is that it is not coupled to the actual shutter mechanism; it is simply a release button block. The shutter itself must be manually cocked for each exposure. If a double exposure is desired, it can be accomplished without using the usual shutter release button on the top. The lever that is actuated by the shutter release button is available on the lower right hand side of the lens barrel/leaf shutter, and the shutter can be cocked and released multiple times without winding the film or engaging the lockup.

Advancing the film is simple and typical of mid-century consumer-grade rollfilm cameras. There is a wind knob on the top left of the camera and a red window on the camera back. The frame number becomes visible through the small red window as one advances the film. The red window has a sliding closure, but I have not yet had a light leak as a result of leaving it open. Even in direct sunlight, it has not resulted in any fogged film.

Another handy piece of operational advice: With any folding camera, make it a habit to open the front of the camera (lens and bellows) before advancing the film. The reason is that upon opening the bellows, air rushing in to the camera creates turbulence that stirs up any dust that may be residing there. Some of that dust invariably ends up on the film. Upon taking the photo, the shadow of that piece of dust becomes a blank spot on the film and a black spot on the final print. That is harder to retouch on a print than a dust spot that occurs in the enlarger during printing, which is white on the print. Any dust that ends up on the film after exposure will wash off in developing with no effect; it hasn’t blocked any light. Of course, if the film is scanned and retouched digitally, it doesn’t matter as much, but dust is still unwelcome, whether in Lightroom or the darkroom.

Overall I have been happy with the Ikonta II. The square image format has always been special to me, and a folder with all its quirks makes for a fun change of pace. It has inspired me to be on the lookout for similar 120 folders, preferably with coupled rangefinders. It would also be fun to have folders in multiple image formats such as 6 x 4.5 cm and 6 x 9 cm. Maybe I keep it, maybe I don’t, but there will always be a place for this type of camera in the cabinet.

Camera specs are as follows:

Designation: Zeiss Ikon Ikonta 523/16 folding camera

Produced: 1952-53 in Stuttgart, Germany

Weight: 594g (1lb 5oz)

Film format: 120, 6x6cm images

Lens: Novar Anastigmat 75mm f3.5

Aperture: 10 blades

Aperture Range: f3.5 to f22

Shutter: Prontor SV leaf shutter

Shutter speed range: B plus 1-1/300 second

Flash Sync: M and X (Bulb and electronic) Sync at all shutter speeds

Rangefinder: none

Light meter: none

Battery: none

Self-timer: yes

Film/ASA reminder: yes